A famous first novel that holds up on its own merits as well as a signpost for a stellar career, Decline And Fall introduces readers to the scathing satire of Evelyn Waugh, where hope is folly, life is a joke, and people regularly suffer for the sin of being alive.

All that, and it manages to be a lot of fun, too.

Often the pleasure of reading first novels by noted authors is twigging onto themes and motifs developed with greater success in their later, more mature works. But Waugh’s debut has no youthful awkwardness to shed. It is fully accomplished fiction, somewhat facile in places and heavy-handedly abrupt in its ending, but masterful in terms of dialogue, description, and mordant observation.

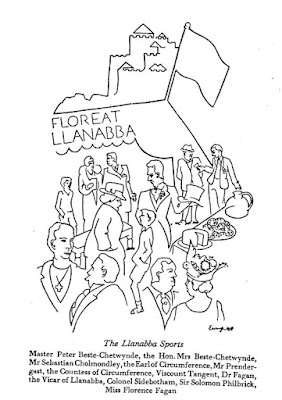

Paul Pennyfeather is an Oxford divinity student who comes to grief when some upper-class twits steal his trousers and get him expelled. With nowhere else to go, he accepts a teaching post at a Welsh boarding school, Llanabba, which caters to problem children of the rich.

It’s not what you teach the children, insists Llanabba’s headmaster, but having what he calls “tone.”

Decline And Fall has tone, too, a bloody whole lot of it. Waugh’s depiction of the boarding school and its Welsh surroundings are presented in a series of deft one-liners offset only by delightfully meandering physical descriptions and a tortured tale worthy of “Ripping Yarns” that raises the bar of comedic misery with every page.

At one point, the school decides to put on an impromptu field day to impress some VIP parents. Since the masters are too cheap and lazy to have acquired hurdles or other track gear to speak of, the boys are lined up and told to run at the sound of the starting gun. This is done with a real gun, by an inebriated teacher who manages to shoot one of the titled youngsters in the foot.

“I knew that was going to happen,” sighs the stricken boy’s noble father.

“A most unfortunate beginning,” comments Dr. Fagan.

“First blood to me!” cries the drunken teacher.

Waugh is very much in his element already. You have the foibles of airhead aristocrats, socially-correct men whose standards of civility make them easy prey for the fairer sex, and quasi-religious concerns expressed by those of little faith for whom Waugh had the clearest contempt, even in the 1920s before he had formalized a deep, lifelong connection with Catholicism.

A would-be Anglican cleric mopes about his lost vocation:

“Once granted the first step, I can see that everything else follows – Tower of Babel, Babylonian captivity, Incarnation, Church, bishops, incense, everything - but what I couldn't see, and what I can’t see now, is why did it all begin?”

Asking his bishop was no help, “he didn’t think the point really arose as far as my practical duties as a parish priest were concerned.”

Pennyfeather is very much in league with later Waugh protagonists, most recognizably Tony Last in A Handful Of Dust and William Boot in Scoop. He initiates nothing; instead things keep happening to him. In fact, Pennyfeather may be the most gormless protagonist we ever got in a Waugh story, not an easy designation to earn.

He’s accurately described at one point as a person “meant to stay in the seats” on one of those Devil’s wheel rides, rather than risk a hard fall by getting too close to life’s unforgiving axle. Pennyfeather merely looks on while others do bad things around him, scarcely curious about the danger they represent to him, let alone the hurt inflicted on others.

Waugh makes clear any sympathy for him is wasted:

…as the reader will probably have discerned already, Paul Pennyfeather would never have made a hero, and the only interest about him arises from the unusual series of events of which his shadow was witness.

Waugh had a somewhat ambivalent relationship with that giant of English novelists, Charles Dickens. In Handful Of Dust, Last is made to suffer by having to read Dickens over and over to a menacing captor who can’t get enough of Little Nell. Here, though, Dickens seems to have been a positive influence, with the entire book jumping from setting to setting like David Copperfield or Oliver Twist.

The scenes at Llanabba are strongly reminiscent of Nicholas Nickleby’s experiences at Dotheboys Hall, except without any moral censure from the author. Waugh instead revels in the corruption on display, of entertaining lies presented as mysterious backstories and a headmaster who pushes Pennyfeather as an organ instructor despite his total lack of musical experience.

“We schoolmasters must temper discretion with deceit,” says this character, whose name Fagan may be another Dickens nod.

Another teacher wears an obvious wig that draws student mockery. This is fine by him, he tells Pennyfeather: “I daresay it’s a good thing to localize their ridicule as far as possible.”

That we eventually move on from Llanabba, never to return, is in keeping with the peripatetic Dickens model, yet the new characters and situations are presented in a more random, plastic fashion. It may be that I just like novels better when they don’t get too antic, a personal failing, but I find Pennyfeather’s adventures with a criminal noblewoman too murky and repetitive, a kind of authorial pile-on.

The latter half of the book does have its highlights. Pennyfeather’s time in prison allows Waugh to send up criminal justice in the same no-holds-barred way he did secondary education in the first half. In fact, he suggests the two are just sides of the same coin.

A reform-minded governor decides to do away with punishment and give prisoners dangerous items like saws to help them learn respectable trades. It is one of his pet theories. A pompous windbag, he lectures Paul and other prisoners about what fine men the penal system will make of them:

“You could see with that unfortunate man just now what a difference it made to him to think that, far from being a mere nameless slave, he has now become part of a great revolution in statistics.”

Of course it doesn’t end well, as Waugh thought less of reformers than he did of Anglicans. Paul meanwhile discovers he rather enjoys prison life. He’s less pressured than ever to do or say anything and misses the outside not at all. He discovers his true calling as a cog in a wheel.

Even newspapers, once a steady pleasure, are not missed:

…for one of the first discoveries of his captivity was that interest in “news” does not spring from genuine curiosity, but from the desire for completeness.

If Decline And Fall has a clear target, it would be modernity, something Waugh would reconcile himself less to the more of it he experienced. The barbs get sharper whenever Pennyfeather’s orbit takes in practitioners of the new.

An architect named Silenus is hired by Margot, Paul’s rich benefactor and later love interest, to rebuild her stately manor house. This estate, King’s Thursday, becomes a lushly-described travesty to avant-garde excess, with vulcanite tables and malachite bathtubs. Professor Silenus is a very future-minded person with some distinct ideas about architecture:

“The problem of architecture as I see it,” he told a journalist who had come to report on the progress of his surprising creation of ferro concrete and aluminum, “is the problem of all art – the elimination of the human element from the consideration of form. The only perfect building must be the factory, because that is built to house machines, not men.”

He even whines at having to include staircases: “Why can’t the creatures stay in one place? Up and down, in and out, round and round!”

The character of Margot Beste-Chetwynde is where the novel loses me a little. She is presented as a force of nature, an indomitable personality who is both a pillar of society and a self-motivating rebel. She is in the end another satirical element, and the one character Waugh kept bringing out in novels to come, but here her presence feels slapped on, inserted for effect rather than organic to the plot.

Issues with the plot and protagonist aside, Decline And Fall is brilliant in the way it develops and maintains its casually caustic tone. It’s played as a broad farce where no one gets off lightly. Given the fact we are closing in on its centennial, the fact it manages not just to be relevant but consistently spark real laughs shows why Waugh was one of the greatest comic writers of all time, up there with Dickens and Mark Twain.

In

time, Waugh branched out from pure comedy to produce more serious and

fulfilling novels like Brideshead Revisited and the “Sword Of Honour”

trilogy. But what he does here is a model in its own right, a bracing prose lampoon

showcasing what greatness an author can achieve when uncompromised either by the sensibilities

of his readers or concern for his characters.

No comments:

Post a Comment