How to rank Nathaniel Hawthorne among the literary giants? He did so much to give serious fiction a uniquely American idiom and character. Yet how many Hawthorne masterpieces are there?

As Mark Van Doren sees it, there are just two. One is widely regarded as the first great American novel. The other, a short story, is just as powerful in the myriad ways it details the evilness of the human heart. Both are majestic, but after that, Hawthorne too often suffered from a willingness to err on the side of comfort, both his own and the reader’s.

Does Van Doren’s minimalist appreciation convince? I don’t think he even tries that hard. But he does offer a bracing way to consider Hawthorne’s deceptively genial legacy from a perspective of eighty years on, a legacy just as bracing eighty years after that.

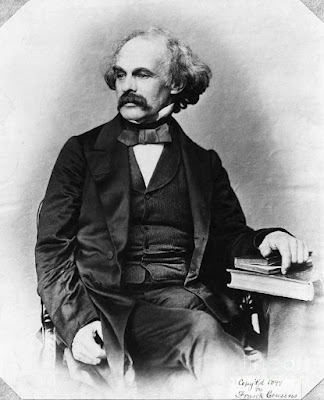

As this is a critical biography, Van Doren’s literary takes are channeled through an engaging, multi-layered account of Hawthorne’s life. Born in Salem, Massachusetts, a town whose spell he struggled to shake his whole life, Hawthorne simultaneously sought engagement with and privacy from a world he regarded with palpable suspicion.

Van Doren quotes an early publisher’s impressions:

“[Hawthorne] was of a rather sturdy form, his hair dark and bushy, his eye steel-gray, his brow thick, his mouth sarcastic, his complexion stony, his whole aspect cold, moody, distrustful. He stood aloof, and surveyed the world from shy and sheltered positions.”

Van Doren, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and leading literary critic of the first half of the 20th century, perhaps enjoyed Hawthorne more than he esteemed him. At least that is the impression this book gives.

Hawthorne was not a man for whom writing for publication came easy, or all that often. He spent most of his abbreviated career struggling to capture greatness in a way the world might recognize. When it happened at last, he suffered further agonies trying, and in Van Doren’s estimate failing, to maintain that exulted level of creativity.

The ability to write “Young Goodman Brown” or, later on, The Scarlet Letter, also strained Hawthorne’s emotional resources in a way that he rarely forced upon himself. Van Doren explains: “The sketches come from the top of Hawthorne’s mind, the part he liked best because it was the gentlest part, the easiest part to live with. It is our luck that he did so with such grace. It is our greater luck that he was forced now and then to go down and live with the devil.”

In making this argument, Van Doren succeeds much better in revealing details of Hawthorne’s life than by reviewing the works themselves.

How does one become a legend? In Hawthorne’s case, it came from rejecting both the past and the present. Spawned by a Puritan lineage with one famously harsh ancestor, Hawthorne did all he could to abjure his inheritance, even altering his last name. At the same time, Van Doren notes a disdain for then-popular dogmas like Transcendentalism, which held out hope for achieving human perfection on earth:

The philosophy which congratulated itself upon having put the Middle Ages behind it was for Hawthorne like the modern clergyman in “The Christmas Banquet” who had “gone astray from the firm foundation of an ancient faith and wandered into a cloud region where everything was misty and deceptive; looking forward, he beheld vapors piled on vapors, and behind him an impassable gulf between the man of yesterday and today.”

Hawthorne’s world view was much bleaker, though most often couched by a sunny pleasantness that camouflaged desperate self-isolation. “His readers who wondered at the world where his imagination was at home could not have known how he in turn wondered at their world: at the world, as he ideally put it to himself,” Van Doren writes.

It is a startling view, one that casts aside the gentler vibes of a writer who achieved first notice crafting sketches designed to please and amuse a growing American middle class. That he didn’t always succeed, commercially or artistically, wasn’t from lack of trying.

The first novel came early, a self-published effort called Fanshawe. It featured a protagonist of the same name whose scholastic life mirrored that of Hawthorne in Bowdoin College. Van Doren calls out its confused tone: “Hawthorne cannot decide whether to offer in this pale form for our melancholy admiration or for our judgment that his way of life, so self-centered and remote, is a grave instance of moral effort.”

Hawthorne later bought all the copies of Fanshawe he could, in order to burn them and thus obliterate them from human memory. This was the fate of many other works that fell short of his lofty expectations. Van Doren ruefully records Hawthorne’s notes to this effect:

“What a trustful guardian of secret matters fire is! What should we do without Fire and Death?”

Hawthorne obscured much of his life to posterity by burning not only sketches and stories but also letters from Sophia Peabody, the woman he eventually married and came to regard as his life’s center. But even she was not always pleased by the dire expression she found in his writing. Her first exposure to The Scarlet Letter sent her to bed in anguish.

One wonders what she might have made of “Young Goodman Brown,” a sketch he produced decades earlier and features at its core a happy marriage built on lies. It also exposes the lies undergirding a seemingly upright community, based both on history and present-day hypocrisy.

“Nothing that Hawthorne wrote came from a deeper source – not even The Scarlet Letter,” Van Doren observes.

The ambiguity of “Young Goodman Brown,” that the exposure of Brown’s community may be more dream than reality, is not for Van Doren. “‘Young Goodman Brown’ means exactly what it says,” he affirms, and later points out the confluent treatment of another Puritan community in The Scarlet Letter.

Here as elsewhere, I think Van Doren underestimates Hawthorne’s willingness to defer a solid verdict but rather involve readers more intimately in the tale’s digestion. Will readers take Brown’s soiled view of humanity as the cold, utter truth or as imbalanced judgment from one too reliant on shallow certitudes? Hawthorne isn’t so definitive.

Van Doren sums up the other tales as preparatory excursions at best and deeply flawed at worst. This is said of even some of the finest ones, short-story masterpieces like “Ethan Brand” and “Wakefield.” “The Minister’s Black Veil” is dismissed in a couple of sentences by Van Doren for its ambiguity (“a certain irresolution in the moral” is how he sums it up, briefly) which I had thought the point.

The stories he likes best are those which anticipate larger works to come. “Peter Goldthwaite’s Treasure” takes place in a big old house, so it prefaces Hawthorne’s approach to The House Of Seven Gables. “Rappaccini’s Daughter” gets real praise (“one of Hawthorne’s greatest tales,” he calls it) but also more attention for its use of an Italian setting, repeated in the later novel The Marble Faun.

In sum, Van Doren’s take on Hawthorne the storyteller is the same verdict Edgar Allan Poe once gave: Too much allegory. “It is his best and his worst device,” Van Doren writes. He notes Hawthorne’s strongest literary influences were John Bunyan and Edmund Spenser, creators of high fantasy but also lightweights in Van Doren’s view.

When it comes to the novels, Van Doren is more appreciative. Even if none reach the mighty summit of The Scarlet Letter, most are worthwhile. Fanshawe is a slight work, yes, but not without charm. The Marble Faun is an exploration of worthy themes, underbaked but full of rich Italian color.

The only Hawthorne novel Van Doren openly dislikes is the one I happen to like best: The Blithedale Romance. The central narrative is thin, the characters are not well-developed, and he hates the narrator:

Miles Coverdale not only tells his story badly – so badly that when he is not forcing scenes he is suppressing them altogether, with the result that we do not know what the story is – but sports and luxuriates in the role of spectator until we lose patience with him…

To me, that unknowable story at the heart of Blithedale Romance is part of its great achievement, along with the circuitous manner of Coverdale. That we don’t quite know whether or not to like him is part of the point, and lends the novel its own shape: modernist, alienating yet involving.

Van Doren is always interesting, especially detailing Hawthorne’s life and its relationship to The Scarlet Letter. That the novel was such an immediate success was the result of the furor caused not by the Hester Prynne story and its indelicate presentation of unmarried sex, but rather because it was prefaced by a section, “The Custom House,” which castigated Salem politicians who had dismissed Hawthorne from his job. The Prynne story itself was what happened when the jobless Hawthorne unleashed his darkest social commentary upon his fickle public.

Van Doren sums up the author this way:

[Hawthorne’s] deathless virtue is that rare thing in any literature, an utterly serious imagination. It was serious, and so it was loving; it was loving, and so it could laugh; it could laugh, and so it could endure the horror it saw in every human heart. But it saw the honor there along with the horror, the dignity by which in some eternity our pain is measured.

No comments:

Post a Comment