A book about historic failure needs a deft hand to keep from being more than a drag for a reader, especially when the topic is the Allied effort in World War II. During the march to final victory, who wants to dwell on an endless spiral of ignominy going on in China?

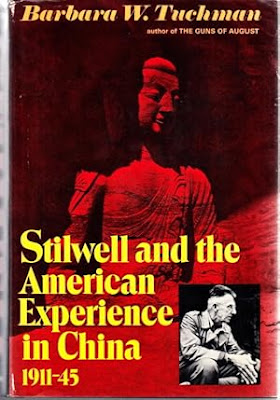

Stilwell And The American Experience In China is not easy to ignore. It was a history of great occasion when it came out, a Pulitzer Prize-winning examination of American policy in the Far East. This came out at a time when young men were being shipped home from Vietnam in body bags by the hundreds every month.

That the book would be seen as all-too-relevant to the politics of the 1970s was not something author Barbara Tuchman avoids. She makes her feelings clear enough in the book’s Foreword:

I am conscious of the hazards of venturing into the realm of America’s China policy, a subject that, following the defeat of Chiang Kai-shek by the Communists and the waste of an immense American effort, aroused one of the angriest and most damaging campaigns of vilification in recent public life. Nevertheless, since China is the ultimate reason for our involvement in Southeast Asia, the subject is worth the venture even though the ground is hot.

Just as her earlier The Guns Of August struck a nerve with its tale of hair-trigger jingoism around the time of the Cuban missile crisis, so too would her thesis here, of Americans butting their unwanted noses into an utterly different mindset and culture.

It is a lesson worth remembering: If you want to make a place safe for democracy, be sure that place wants democracy first.

U.S. Gen. Joseph Stilwell is an unlikely hero of the book, a sensible, optimistic advocate for action who had difficulty getting along with people he didn’t respect. This included many fellow generals, especially British ones, and the recognized leader of China, Chiang Kai-shek.

Stilwell nicknamed Chiang “Peanut” on account of his short stature and bald head. The fact that got around tells you something about how Stilwell handled his assignment. “We are doing our damnedest to help him and he makes his approval look like a tremendous concession,” he fumed about Chiang. Stilwell did not hide this displeasure.

That is the meat of the book. After introducing us to Stilwell and his earlier tours of duty in pre-war China, Tuchman settles into a long account of one man’s losing struggle to get the leader of the world’s most populous nation to fight back against a murderous Japanese invader. It was a lost cause, Tuchman explains, because Chiang had no interest in fighting Japan. Rather, he wanted to sponge money and supplies for another war to come, against Chinese communists up north:

Believing that the war could be won for him without his additional effort, Chiang predicated his policy in so far as he had any, on survival in power while the Japanese were defeated by the Allies outside China. As far as the external enemy was concerned, he had made a shrewd, and as it was to prove, a sound calculation.

Sound only that Chiang was able to parlay U.S. material support into a wealthy island exile after he got kicked off the Chinese mainland.

In Tuchman’s telling, Chiang was a stubborn, conceited man, not cut out for the job he had. Post-imperial China was a warren of feudal lords and crime bosses, all skimming from peasants and resisting the need for change. Only the communists under Mao Tse-Tung had both the will and vision to bring forth a better future for their country.

At least that’s Tuchman’s take. Would it have been Stilwell’s?

He was a conservative Republican, skeptical of communism and even disdainful of the progressive Democrat in the White House. His attitudes were of their time, blinkered and occasionally racist by the standards of the 1970s, let alone today. While acknowledging all this, Tuchman presents Stilwell as a model of noble insight and liberal impulse:

Face to face with the old and limitless misery of China, Stilwell wrote with truth and understanding in contrast to the rather banal ideas he expressed on social problems in America.

Tuchman was given access to Stilwell’s journals by his family and drew from them freely. The result is a book that presents Sino-American relations from a single, subjective prism, valuing those Stilwell encountered mostly by how much he liked and respected them.

This was no easy thing. Stilwell had a skeptical disposition which earned him the nickname “Vinegar Joe.” “He did not have the tact or capacity to deal with opinions which he held in contempt, and contempt came to him easily,” Tuchman writes. Except in a rare case like President Roosevelt, the author mostly echoes Stilwell’s judgments.

It is here the book suffers. Even if one acknowledges the validity of her central thesis that Chiang was a short-sighted dictator who cared more about his bank account than his country, pushing this point feels wrong. Her narrative is one-sided to the point of repetitive dullness. She criticizes Chiang for failing to fight, but when his forces do fight, and well, she blames him for the lives lost in stalemates.

The most Tuchman offers on Chiang’s behalf is that he felt his sovereignty belittled by Stilwell’s often caustic counsel. Her focus is on the wastefulness of American involvement in China, but the takeaway I had was the folly of giving such a delicate job to a man like Stilwell. As generals go, he lacked the strategic tact of Eisenhower.

A tragedy of Stilwell And The American Experience In China is that Stilwell was a doughty commander, brave and canny in combat, who could have been a boon to the Allied cause in any other theater of operations. He understood the problems of the terrain where he fought, both in China and in Burma, and managed well under the circumstances.

“The Chinese soldier is excellent material, wasted and betrayed by stupid leadership,” he is quoted saying. In fact, after years of reeling and dying under Japanese attack, the Chinese led by Stilwell did manage in 1944 to seize a Japanese stronghold in Myitkyina, a major Burmese transit hub. But before this victory could be exploited, Stilwell was gone, a victim of Chiang and those Americans who supported Chiang.

Tuchman presents China as an impossible mission:

American saw it in the Chinese a people rightly struggling to be free and assumed that because they were struggling for sovereignty they were also struggling for democracy. This was a delusion of the West. Many struggles were going on in China – for power, for nationhood, even in some cases for the welfare of the people – but election and representation, the sacred rights on which Westerners are nursed, were not their goal.

Tuchman’s focus often strays from matters of the war. It is here her animus becomes most clear, not for Chiang but rather the American right who later used China’s fall to stoke the fires of McCarthyism.

At several points, she questions the preference of Roosevelt and Stilwell for dealing with Chiang rather than Mao, who after all showed more willingness to fight: “What course Chinese Communism might have taken if an American connection had been brought to bear is a question that lost opportunities have made forever unanswerable. The only certainty is that it could not have been worse.”

This sort of prosecution by hindsight is common to Tuchman’s histories, especially later ones. But relying on the story alone may not have worked here. A great soldier comes to a foreign land to bring its army to a state where it can fight, only to fail and be sent away. The end.

The book is at its best at the beginning, when Tuchman explains how China appeared to a young Westerner in the early 20th century (she and Stilwell were both there in the 1930s). It was a nation chewed up both by Western greed and its own warlords, where poverty was constant and the price of weakness steep:

Death was as common as the windblown dust of China, its reminder everywhere in the grave mounds that would wear away over the centuries to be plowed back into the fields, its visible presence in the corpse of a girl baby, victim of infanticide at birth, laid out unburied between the grave mounds for dogs to eat.

Any impulse to do good had to be resisted, however, in Tuchman’s view, at least for outsiders. She suggests a large population makes China less moved by individual tragedies, that as the world’s oldest culture it historically takes a long view. When the Japanese attacked, it was much like the 18th century invasion of European powers, a thing to be endured and waited out. The Chinese ability to survive and prevail was paramount.

Stilwell was no gormless do-gooder; in Tuchman’s

estimate he brought a level head to an intractable problem, and a determination

not to give up. Unfortunately for him, he was better off leaving the situation

to others. Though Stilwell did get a combat command after returning from his

China post, he was not to see action again before war’s end. He would die less

than a year later, his body worn out from cancer and strain.

Whether building a road in west-central China or leading a march of war refugees, Stilwell is presented as a compelling central figure for some worthy adventure stories well-told. He just didn’t fit the bill for the assignment, one Tuchman ultimately, grudgingly seems to acknowledge.

No comments:

Post a Comment