Can a book’s credibility be hobbled by privileged access to its primary subject? Can that same access, used to its fullest degree, redeem the book’s faults and render it an enduring classic?

Yes, and yes. Here’s the proof.

Covering the 1960 Presidential election, Theodore White interviewed John F. Kennedy, flew with Kennedy, ate with Kennedy, gossiped with Kennedy. He did everything but sleep with Kennedy, though he does wind up in bed with the guy here, figuratively speaking.

It was for a good cause. This book remains not only a vital record of one of the country’s most charismatic politicians but a deep dive into how a presidency could be won. Even White later admitted he got carried away, but his invested narrative and sense of purpose pull you in.

White presents a profile in courage. On a desolate Wisconsin road early in the campaign, Kennedy fights off sleep and depression by quizzing his driver about the fish in Lake Superior. Later, in the small community of Philips, he is undaunted by the handful of bored onlookers who greet him. “He left the town shortly after noon and the town was as careless of his presence as of a cold wind passing through,” White writes.

Yet Kennedy stays the course. Over time, this decorated war veteran and PT-boat commander finds himself riding out a storm as a Catholic candidate for a job thought exclusive to Protestants. With his elegant wit and undaunted spirit, Kennedy proves himself a man of the moment. In White’s telling, he was literally born for greatness:

He had mastered politics on so many different levels that no other contemporary American could match him. He had nursed ward politics with his mother’s milk; heard it from his grandfathers, politicians both, in boyhood; seen it practiced from his father’s embassy in London at the supreme level of world events in 1939, as war and peace hung in the balance.

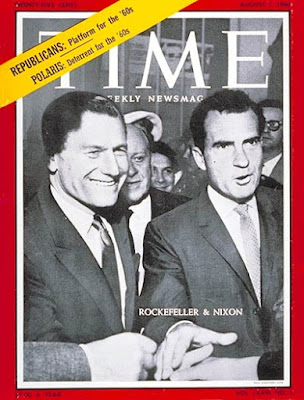

Meanwhile, his eventual Republican opponent, Richard Nixon, is depicted in unflattering detail addressing an audience “the way the man in a white smock selling an analgesic does on the television screen.”

It’s slanted stuff, but compelling. Before The Making Of The President 1960, writing about presidential races was stiff and by-the-numbers. White saw the potential for capturing a democratic nation in transition, drawing upon all the hothouse drama and character that tended to get swept away with the ballot stubs after Election Day.

Whether Kennedy fundamentally changed the nation, before or after his win, is debatable. Yet in 1960 his youth and vigor (“vig-arh” as Kennedy put it), not to mention the many youngish faces the candidate attracted, stimulated hopes in White and many others:

They had planned shrewdly and skillfully in this room on that long-ago October day of 1959 to direct a campaign that would sweep out of the decade of the sixties America’s past prejudices, the sediment of yesterday’s politics, and make a new politics of the future.

The first man born in the 20th century to win the presidency, Kennedy seemed to augur a transformation of the Republic from stolid, old-fashioned virtues to something fresh and dynamic, a compassionate liberalism willing to push more than public works and social spending. He challenged Americans to be more while giving voice to healing racial divides and fostering a foreign policy of hope and vision.

At least that is the story White tells.

What really happened was more complicated. Kennedy was not the liberal in the race, certainly not in the primaries, maybe not after.

Fighting for the Democratic nomination, Kennedy let Senator Hubert Humphrey and former presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson run as progressives. Both Humphrey and Stevenson get their moments in White’s book, but mostly by way of unkind comparison:

With Humphrey, the liberal lion of the Senate, all too eager to tout his causes, familiarity bred contempt: Humphrey yearned for the attention of the national press; yet the national press, which bore him so deep an affection, considered him almost too easy a friend.

White’s take on Stevenson is even more cutting: Yet public affairs and politics are linked as are love and sex. Stevenson’s attitude to politics has always seemed that of a man who believes love is the most ennobling of human emotions while the mechanics of sex are dirty and squalid.

Lyndon Johnson put it another way in one of Robert Caro’s biographies, “He’s a nice fellow, Mother, but he won’t make it ‘cause he’s got too much lace on his drawers.”

Johnson was another top candidate, the Senate Majority Leader who like Stevenson sat out the primaries waiting to be anointed at the Democratic National Convention. That was how it was done then. For too many, White says Johnson was seen as a “race-prejudiced Southerner” even with a record more positive on civil rights than liberal critics admitted. Besides, “To watch Lyndon B. Johnson perform oratory on his native heath is to see something like an act out of a show-boat production.”

You wouldn’t know it reading White, but the issues that helped Kennedy’s case against Nixon were often found by tacking to the right. Kennedy argued that the United States was falling behind in missile production, and that it was losing ground to communism because of a soft and directionless foreign policy. That explains why, so early in his young presidency, Kennedy felt so compelled to invade Cuba.

White has no time for Kennedy the Cold Warrior. His Kennedy acts immediately when Black leader Martin Luther King Jr. is jailed in the South, even fending off a possible lynching in White’s account, and becomes deeply moved by the sight of the Appalachian poor while campaigning in West Virginia:

“Imagine,” he said to one of his assistants one night, “just imagine kids who never drink milk.”

All this is factual, but highly subjective, in the same way Nixon is depicted muttering endless banalities on the campaign trail. You wonder how the election wound up being so close, just 111,000 votes, or as White puts it “so thin as to be almost an accident of counting.”

White rewards our indulgence with a deeper portrait of his man, one that goes beneath the skin to reveal a tactile, brusque emotional quality.

Kennedy gulps down clam chowder the same way he does newspaper columns and is always eager to corner a correspondent on a plane about what’s being said on the trail. Kennedy’s dislike for Nixon was real, we are told, not put on for the campaign. He attracts a team of highly-skilled men, each of whom is bedecked with multiple superlatives from White:

In the personal Kennedy lexicon, no phrase is more damning than “He’s a very common man” or “That’s a very ordinary type.” Kennedy, elegant in dress, in phrase, in manner, has always required quality work; these men by his standards were extraordinary; they were his choices.

White opens with the view of the ocean from Kennedy’s home compound in Hyannisport, Massachusetts, grey waves rolling in while Kennedy watches them and millions watch him. He displays a spry wit and calloused hands from months of reaching out to voters.

Over the course of the book, White stresses again and again the effort it took for Kennedy to win, overcoming prejudices against both his religion and youth. There are moments of grave doubt, but through it all he never loses focus and stays the course.

Kennedy would be called the first President to win office by television, a verdict that still gets debated. Did Kennedy outperform Nixon in all four of their network-broadcast debates, or just the first? And was it a victory only if you watched them, rather than heard them simulcast on radio?

White notes Nixon did have cosmetic problems, like sweatiness and a persistent five-o’-clock shadow, but also an insular speaking style. He contrasts that with Kennedy’s forceful attack in every debate, seeing no room for doubt as to who won all of them in stride:

“Every time we get those two fellows on the screen side by side,” said J. Leonard Reinsch, Kennedy’s TV maestro, “we’re going to gain and he’s going to lose.”

White’s book is a useful primer for many things that resonate today, like media bias. For Nixon and his campaign, it was real and a source of deep resentment. White describes how Nixon refused to talk to him, or to many reporters while he was flying with them to his campaign stops, and clearly bristles at this refusal.

Meanwhile, Kennedy and his people made cheerful company:

To

be transferred from the Nixon campaign tour to the Kennedy campaign tour meant

no lightening of exertion or weariness for any newspaperman – but it was as if

one were transformed in role from leper and outcast to friend and battle

companion.

The Making Of The President captures a media transforming into the janissariat for liberal elites mostly unknowingly, but it is tempered throughout by White’s honest pursuit of a good story. Far from perfect history, but a brilliant first draft that keeps its history alive.

No comments:

Post a Comment