People who complain about the use of sabermetrics in baseball miss the art of the matter. Statistics tell a story, lots of stories, all awaiting a chance to delight and deepen your appreciation of the game.

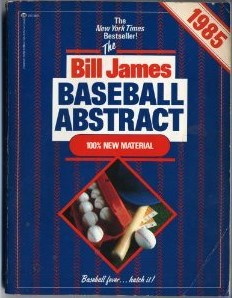

Normally this is where I bring in Bill James as my guru, whipping out often amusing, sometimes astounding facts from endless seas of data. So what can I say when he delivers a book so tiresome that it makes the naysayers seem like they have a point?

The Bill James Baseball Abstract 1985 is a mash of stats and knee-jerk opinion posing as sober analysis, written by a huffy author with too many irons in the fire. At the same time James was producing this, his annual look at the past year in Major League Baseball, he was also publishing a newsletter, undertaking a grandiose project to collect scoresheets from every MLB game ever played, and writing the manuscript for what became the Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract.

James’s disengaged prose tells me that he’d rather be writing his Historical Abstract. In the last pages of Abstract 1985, he just about says so in the way of plugging his forthcoming tome:

I like the book – in fact, I like that book quite a bit better than I like this one…This is probably the heaviest and most technical book that I’ve written, and I’m not real pleased with it in that respect – but the other one is certainly the lightest and least technical book, and the most fun book, that I’ve done.

That is true. The Historical Abstract, particularly its first edition, is a masterpiece, James’s crowning achievement of bringing together compelling analysis with deep-dish appreciation for the lore of the game. Every page has something to savor, and the stat-mining is minor. The 1985 Abstract must have been a chore to write, for it is a bore to read.

The bulk of the 1985 Abstract, like the others before it, consists of long chapters on how each team in Major League Baseball performed in 1984, which of their players had the best seasons, and what can be expected of them in 1985. But this time, instead of producing those insights all by himself, James left it to other writers to write many of these team analyses, non-sportswriters with whom he had corresponded.

So we get analysis on the New York Yankees from one Craig Christmann, a deep look at what happened when the Toronto Blue Jays and their opponents put the first ball in play by David Driscoll, and examination of the problem the Milwaukee Brewers have finding a reliable leadoff hitter by Scott Segrin. It’s not why I buy a book with the name “Bill James” on the cover, but anyway.

The write-ups are good to fair, not written with the same wit or accessibility James gave me but serviceable. But then at the end of these chapters you do get James himself, weighing in with what he calls “editor’s notes,” which often call out his collaborators for fuzzy thinking or otherwise dismiss them. Not only is this classless, it is lazy.

When Tim Mulligan tries to explain a concept he calls “Victory Important RBI” as it relates to the Baltimore Orioles’s 1984 season, James jumps in to squash him like a bug:

I don’t understand the [Mike] Young/[Gary] Roenicke comparison at all. I don’t see how in the world Mr. Mulligan infers Young’s “versatility” from the fact that Roenicke drove in more runs per at bat, nor do I see what it has to do with the current subject.

Here’s a thought, Bill. Call Tim and ask him. Be an editor and edit the piece he submitted for your approval so it does make sense to you. But no, that would have been work, and James was busy enough with the more important Historical Abstract. At least that is how I read it.

What else can be made of brilliant, probing insights like this: “About the present [Cleveland] Indian team, I have little enough to say.” Just wow!

James usually has a couple of terrific new formulas to present in these books. Here he starts the book with something he calls “the Brock2 system,” a means of projecting future player performance by how they have played to date. Naturally, he works backwards by showing the reader how well such a system anticipates such things as career batting average, longevity, and other metrics based on a few seasons.

“Whether or not it is a scientific method depends on how you define the word ‘science,’” he says, adding he can not make any claims to its validity until further testing. In other words, it is not ready for prime time, an impression the handful of cherry-picked examples does not shake. His only reason for debuting it now is to take up space.

Other disappointments include a segue into the matter of good-hitting pitchers when discussing the Pittsburgh Pirates, who in 1984 had two of the best hitting pitchers in the majors, Don Robinson and Rick Rhoden. James spends three pages on the subject before throwing up his hands and concluding: “A pitcher’s ability to swing a bat plays a very minor role in determining his ability to help the team win, and thus in determining his value to the team.” So why the three pages?

Meanwhile, the fact that the 1984 Pirates pitchers had managed the heretofore unmatched feat of leading the National League in lowest earned-run average while simultaneously finishing at the bottom of the standings gets a brief paragraph, without any attempt at explaining how or why. The 1985 Abstract is that kind of book.

As a New York Mets fan, I was particularly keen to read the 1985 Baseball Abstract because the 1984 season was the start of the longest sustained string of successful seasons my fanhood was ever to know. That season saw the Mets break through after a seven-year losing drought to win 90 games, good enough for a second-place finish.

How would Bill James help put this glowing memory of youth in proper context for me? Why, by handing the mike off to Mets fan and correspondent Bill Deane, who worries the team did it with smoke and mirrors and will return to a sub-.500 season in 1985. James jumps in to temper this gloomy forecast, noting the arrival to the team of Gary Carter, his pick for best MLB catcher since Yogi Berra. But it all amounts to little more than a shrug, “they’ll-be-fine” kind of thing.

The team that won everything in 1984, and did so with such gusto, was the Detroit Tigers, basically shutting down the American League East race in June. Here James had a dilemma. The Tigers’s manager, Sparky Anderson, was someone he had singled out in past Abstracts as a weak skipper, getting less from his team than was there because he was too relaxed and stuck in his old-ball ways.

Here James admits to being caught flat-footed by the team’s success, saying he didn’t follow his own formulas enough to trust the team’s white-hot April and May stretch. He barely addresses the fact he dissed Sparky. Instead, he plays up the team’s talent, a take consistent with his past views, if a bit overstated here:

As much as one can tell by making systematic position by position comparisons, the individual talents of the 1984 Detroit Tigers are substantially as solid as any in the last 25 years. There is no good reason that I can find not to conclude that they are in the same general class as the 1969-71 Orioles, the 1972-74 A’s, the Big Red Machine and the Yankees that all the books are written about. They probably are substantially superior to the 1961 Yankees and the 1967 Cardinals.

The only reason I can find not to conclude that is while the teams he mentions all made multiple World Series, the Tigers of the 1980s did not. At least James’s breakout of the different lineups is engaging if glib.

A more penetrating examination is offered of the Kansas City Royals, who lost to the Tigers in the 1984 American League Championship Series. James notes the Royals were the first team to win their division while scoring fewer runs (673) than they allowed (684). He then spends some time trying to deduce how this happened.

His conclusion seems to be that they were an “overefficient” team, i. e. underperforming players getting lucky, and due to fall back to a more mediocre level like other such teams normally do the following season. The 1979 Philadelphia Phillies did win the World Series in 1980, he adds, “but you can base a hope on anything you want to.”

James is a Royals fan, so I suppose he wasn’t too unhappy to find himself shown up by the 1985 Royals taking the MLB crown. They were the only returning division winner to boot, so not a fluke.

In other places, James is pithy and good for a smart soundbite. Weighing in on a clubhouse issue where Minnesota Twins players singled out teammate Chris Speier for poor play during a pennant drive, he notes: “When you see a contending team start looking around for a scapegoat, you’ve got a real good clue that a scapegoat will soon be needed.”

Or on speedy superstar Rickey Henderson leaving Oakland to join the New York Yankees:

Had I been running the A’s, my first priority would have been to do everything I could to see that Rickey Henderson would die in a Oakland uniform. My second priority have been to see that he lived as long as possible.

James could always write well, only before he managed entire essays. In the 1985 Abstract, the best you get are bullet points. His focus would return to the benefit of later Abstracts; it is sorely missed here.

No comments:

Post a Comment