Have you ever re-read one of those books they used to assign you back in school? Did you ever notice how almost-uniformly unpleasant they are to read today?

The Painted Bird is the most wretched of them, but there were a host of suicide stimuli on offer back in my day: The Lord Of The Flies, A Separate Peace, Crime And Punishment, The Bell Jar, The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter and of course this story about what happens when an oppressed group of animals take over a farm.

Did they want to put us off reading forever? Did they want social media to take over the planet before it had even been invented?

Somewhere in England, Manor Farm is run by a Mr. Jones, who drinks a little. One night, a prize pig named Old Major gathers the other animals around his bed of straw to tell them of the terrible fates Mr. Jones has in store for them. Accepting this, he adds, is not in their interests:

“Is it not crystal clear, then, comrades, that all the evils of this life of ours spring from the tyranny of human beings? Only get rid of Man, and the produce of our labour would be our own. Almost overnight we could become rich and free.”

Old Major also instructs them on needed principles for running a new Man-free farm, and even teaches an inspiring song, “Beasts Of England.” Days later Old Major is dead, but his dream lives on. Led by two other pigs, Snowball and Napoleon, the animals kick out Mr. Jones and take over Manor Farm. Adopting a no-kill, all-animals-are-equal policy, they give their place a new name, Animal Farm.

The subtitle of this book, “A Fairy Story,” portends a parable. Its harrowing opening of Major telling the animals they are soon to be butchered if they let life play out in its accustomed way (“You young porkers who are sitting in front of me, every one of you will scream your lives out at the block within a year.”) strongly hints at an overarching vegetarian message, but Orwell has other fish to fry.

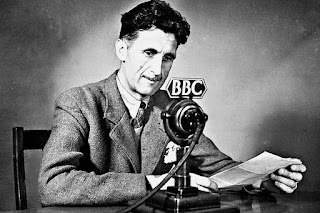

At the time he wrote this, the specter of Soviet communism was on the ascent. Animal Farm is Orwell’s famous indictment of that brand of government, specifically as practiced by Joseph Stalin, presented here in the form of opportunistic and ruthless Napoleon.

For Orwell, as a political progressive and committed socialist, the parallel was clear between animals toiling and dying for the benefit of human masters and the ways of Western capitalism. Communism was not his answer, though. Orwell saw that as a different kind of threat, more insidious in the way it incorporated idealism and language to plot against the liberties and lives of its subjects.

Or maybe it was just Stalin himself Orwell didn’t like. To tell the truth, it’s difficult to be sure reading Animal Farm what Orwell was against.

Let’s get something out of the way, I don’t like this as a story. Its tone is too grim. Despite ample opportunities for Swiftian satire, humor is limited to Napoleon’s zest for liquor. The plot is one-note and mundane.

Even the expulsion of Mr. Jones and his men is presented perfunctorily:

After only a moment or two they gave up trying to defend themselves and took to their heels. A minute later all five of them were in full flight down the cart-track that led to the main road, with the animals pursuing them in triumph.

Orwell wasn’t invested in world-building, unlike fellow thinkers C. S. Lewis and L. Frank Baum, whose effervescent fantasy constructs are why, respectively, “The Chronicles Of Narnia” and “The Wizard Of Oz” are celebrated today. Orwell’s concern is purely philosophical, making very specific parallels and foregoing the fantasy. Orwell doesn’t lay out Animal Farm in any way, or itemize its features, except for a windmill the animals build, intended as a sort of analogy for the Soviet five-year modernization plans.

I don’t even think this works. Napoleon is Stalin, but who exactly is the other pig, Snowball? It seems Orwell combined two major figures of the November Revolution, founder Vladimir Lenin and his deputy, Leon Trotsky, but they came to very different ends. The former died from illness while still in power, the latter was kicked out by Stalin and eventually murdered in Mexico by a Soviet agent.

Snowball is the pig who makes things happen in Animal Farm, the one with the necessary vision and the courage. Napoleon hangs back and takes the credit. Orwell clearly admires Snowball’s leadership, though it isn’t perfect; cows’ milk is stolen from the farm’s collective resources to make apple mash exclusively for the pigs’ enjoyment. Other than that minor taint of corruption, Snowball is committed to the noble ideals of Animal Farm and hard not to like.

Lenin and Trotsky’s histories were much more nasty. During the Red Terror, they were responsible for the killing of many thousands of farmers and dissidents, waged war on Poland, and centralized power at least as aggressively as Stalin would later, when he was given more time. They also crushed the Mensheviks, the more moderate socialists who paved the Soviet path to power by overthrowing Czar Nicholas II.

None of this shows up in Animal Farm. Orwell hurries to get to the point of the book, that Napoleon (Stalin) is an evil and greedy pig. So he removes any difficulty from Napoleon’s rise to power. A human invasion is beaten off with ease. Snowball is chased off the farm as briskly as was Mr. Jones. And as Napoleon’s chief lackey Squealer rewrites the list of Commandments which hang over the farm, the animals are mostly too stupid to notice this and other Big Lies, or too easily misdirected if by chance they do:

Afterwards Squealer made a round of the farm and set the animals’ minds at rest. He assured them that the resolution against engaging in trade and using money had never been passed, or even suggested. It was pure imagination, probably traceable in the beginning to lies circulated by Snowball.

Orwell does draw extensively on one element of Soviet history, as Napoleon plays off a pair of neighboring human farmers. These are Mr. Frederick of Pinchfield Farm, standing in for Germany; and Mr. Pilkington of Foxwood Farm, supposed to represent Great Britain:

Napoleon was hesitating between the two, unable to make up his mind. It was noticed that whenever he seemed on the point of coming to an agreement with Frederick, Snowball was declared to be hiding at Foxwood, while, when he inclined toward Pilkington, Snowball was said to be at Pinchfield.

This becomes a very labored and malnourished sidebar of the story. Stalin’s dealings with Germany led to a non-aggression pact, the splitting up of Poland, and a surprise attack by Germany which left millions dead; in the story, Napoleon is swindled with counterfeit currency and then briefly invaded by the forces of Mr. Frederick, something Napoleon is able to shrug off by claiming victory.

Later, when Napoleon aligns with Mr. Pilkington, he does so by openly denouncing Animal Farm’s founding ethos. The most Stalin ever did to ease his hardline Marxism was allow the Russian Orthodox Church to practice openly again, which Orwell satirizes in the form of an obnoxious crow named Moses who spreads lies about “Sugarcandy Mountain” and is tolerated by the pigs because his religious cant placates the Farm’s dumber animals.

Of course, this isn’t meant as a point-by-point takedown of Stalinism; it’s a fable. It just doesn’t work for me in that department, either.

Orwell’s disinterest in his characters, animal or otherwise, is palpable and annoying. Napoleon says very little; he acquires his position through brute force. Most of the farm animals meekly follow his rule, even those he opts to execute after show trials. The noble but stupid horse Boxer reflects the general sentiment with his maxims “I will work harder” and “Napoleon is always right.” When Boxer meets a terrible fate as the price of his loyalty, he’s too one-dimensional a character for it to be anything other than his own stupid fault.

What makes Animal Farm interesting for me is how it prefigures concerns Orwell addresses more deeply in his subsequent and final novel, 1984. While terms like “police state” and “newspeak” are employed in 1984 and not here, Animal Farm does present the misuse of language and scapegoating as dictatorial tools.

We see this in the Farm’s motto, reworked by Napoleon: “ALL ANIMALS ARE EQUAL/BUT SOME ANIMALS ARE MORE EQUAL THAN OTHERS.” It shows up elsewhere, too; the constant blaming of calamity on Snowball and the verbal gamesmanship of Napoleon’s mouthpiece, Squealer, who “corrects” confused listeners whose memories don’t accord with the now-official version.

By book’s end, hardly anyone remembers how bad life was under Mr. Jones; their chronic forgetfulness further empowering Napoleon:

Only old Benjamin professed to remember every detail of his long life and to know that things never had been, nor ever could be much better or much worse – hunger, hardship, and disappointment being, so he said, the unalterable law of life.

As satire, Animal Farm lacks humor; as a fable, it wants for joy and wonder; as a political tract, its once-bracing originality has faded into a cynical shrug. Even most communists today don’t like Stalin and aren’t afraid to say so.

The premise of Animal Farm is fantastic; a fairy tale reworked as political satire should have been a treat. But Orwell’s cold precision and clinical detachment make for a dreary ordeal, and the hard lessons it teaches are those of futility and pain. Why did miserable books like this find their way on so many classroom syllabi? I can only hope teachers today employ books their students have a fighting chance of liking.

No comments:

Post a Comment