Before he wrote this, his most famous work of fiction, J. D. Salinger wrote a short story entitled “This Sandwich Has No Mayonnaise.” Which is funny, because an alternate title here could be This Novel Has No Plot.

It features a problem student stuck in a rut. Either Holden Caulfield is stumbling through serious adjustment problems, or he is pretending they don’t exist, but those issues are there and form the basis of the story.

The real problem is that story, or lack thereof. Salinger’s remarkable abilities at developing characters and settings are on vivid display, because his one and only novel is a dead loss in the plot department.

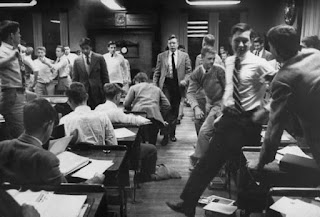

Sixteen-year-old Holden is about to get bounced from Pencey Preparatory Academy, an elite boarding school in Pennsylvania. He doesn’t lack intelligence; he just can’t be bothered with classwork. Something is bothering him, and he can’t or won’t let it go. Fed up, he escapes to New York City, where his family lives.

Life, it seems, just has a habit of letting him down:

I mean I’ve left schools and places I didn’t even know I was leaving them. I hate that. I don’t care if it’s a sad good-by or a bad good-by, but when I leave a place I like to know I’m leaving it. If you don’t, you feel even worse.

Back home in Manhattan, Holden rides taxicabs and visits Central Park, pondering such mundanities as where the ducks go in the winter. He strikes up conversations with strangers, hires a prostitute and gets a beating after he tries just having a conversation with her, and finishes his night dropping in on his little sister, Phoebe, his beacon of innocence in a fallen world.

“When in hell are you going to grow up?” Holden is asked. Unwilling to accept pending adulthood, he is content to skate through life, burdened with the memory of a beloved dead brother, knowing he’s heading off a cliff but unable to care.

It’s a coming-of-age novel that connects with many readers, including me back when I first read it. When Holden is walking the rain-slick streets of Manhattan in the dead of night, you feel it like an Edward Hopper painting. His conversations with other students at Pencey have a lived-in quality and humor so keen you wish Salinger kept Holden there longer. His mood swings, his awkward but sincere articulation, his sudden impulsiveness, all carry with them the fragrance of youth.

Where it falls flat is in its failure to cohere or sustain momentum.

Take the opening chapter. You might expect the opening chapter of such a first-class novel like this to pull you in immediately. I know Moby-Dick left me cold, but like a lot of people I still can remember its first three words.

Does anyone remember how Catcher In The Rye begins? I was surprised.

After explaining he is now in an institution somewhere, Holden begins by mapping out the parts of his life he will not discuss, like his birth and upbringing and “all that David Copperfield kind of crap,” focusing instead on the day he left Pencey Prep. So what happens in the first chapter? He describes a big football game against Saxon Hall, how he sat apart from the other students for a time, got annoyed by all the demonstrations of school spirit, and eventually walked off to say goodbye to a teacher who had befriended him.

End of chapter.

You do get a lot of information about Holden, as he is always distracted in his narration and recalls things from his past with the faintest connections to what he is experiencing now, which he relates in some detail. But the chapter itself goes nowhere. It sets the tone, but it’s a rather downbeat tone that clings like moss to the rest of the book. Looking for growth? You’ve come to the wrong classic.

Even that meeting with this teacher proves a dead-end itself at the end of chapter two.

Catcher In The Rye eventually establishes itself as a series of digressions: “The trouble with me is, I like it when somebody digresses,” Holden explains late in the book. “It’s more interesting and all.”

I thought so, too, when I was 14. Today, I find my patience taxed by a storyteller who never gets to the point of anything.

Holden proves frustratingly unlikable in his pettiness and narcissism. You don’t need a likable protagonist, but not having one is death in a novel that never goes anywhere.

He stresses his discomfort with the exclusionary practices of others. Only he has a nasty habit of looking down on everybody, especially those older and poorer than he:

The bellboy that showed me to the room was this very old guy around sixty-five. He was even more depressing than the room was…Anyway what a gorgeous job for a guy around sixty-five years old.

Often Holden is vague or obtuse at expounding on some concept he can’t quite explain that is meant as a window on his fragile emotional state. Because these reveries are served up so cold and vague, they come off affected:

New York’s terrible when somebody laughs on the street very late at night. You can hear it for miles. It makes you feel so lonesome and depressed.

Holden spends much time railing at societal norms. It’s important here to acknowledge Holden’s shrillness on the subject is something Salinger intends as irony; while Holden vents that “People never notice anything” you are simultaneously noticing how antic and exposed Holden has made himself, whether by loudly badgering a casual acquaintance in a crowded bar about sex or trying to strike up a conversation with three female tourists who can not contain their boredom with him.

The boy just can’t help himself, like when he brings the prostitute to his hotel room:

She was a lousy conversationalist. “Do you work every night? I asked her – it sounded sort of awful, after I said it.

Salinger’s sense of humor is a saving grace throughout the novel, most especially in the first half, when he is expounding on Pencey Prep and all the “phonies” there. (“That guy Morrow was about as sensitive as a goddam toilet seat.”) As the novel goes on, Salinger’s heavy investment in his character deepens. Holden is given to passages of long and serious deep thought that render him insufferable:

God, I love it when a kid’s nice and polite when you tighten their skate for them or something. Most kids are. They really are. I asked her if she cared to have a hot chocolate or something with me, but she said no, thank you. She said she had to meet her friend. Kids always have to meet their friend. That kills me.

Maybe it is a product of getting older. Or maybe it is noticing how the book functions as a series of false starts, Salinger beginning to round on a situation only to let it go. Holden visits a place and meets some people, he finds them disappointing somehow, he wanders on and meets someone else.

Mostly he complains about how things never stay the same, a familiar complaint that hits me more the older I get, but doesn’t make Holden any more relatable or his company more palatable. His manner is so odd and off-putting:

Certain things they should stay the way they are. You ought to be able to stick them in one of those big glass cases and just leave them alone. I know that’s impossible, but it’s too bad anyway. Anyway I kept thinking about all that while I walked.

This line of thought eventually culminates in one of the book’s most famous monologues, the one that gives it its enigmatic title. Holden wishes he could just be at the bottom of a cliff all his life, catching smaller children falling off a field of rye where they frolic in endless play, thus protecting them from danger.

Does anyone really know what Holden (or Salinger) was on about here? It’s a metaphor for innocence, I guess, but a strained one, excused only by the fact our narrator is in such rough shape: “I swear to God I’m a madman.”

I do still find Catcher In The Rye entertaining. Reading it brings back my own surprisingly fond recollections of teenage dislocation, frightening as they were to live through. But in so many ways I find it lacking. The novel builds up to a pair of major encounters – with Holden’s parents and with a girl he fancies named Jane Gallagher – but we never actually see a meeting with any of them. Meanwhile, the people he does talk to tend to disappear unnoticed.

This may itself be a closet commentary by Salinger on the ephemerality of life, especially as lived by Holden, but if so, it provides a handy excuse for a lazy narrative.

The Catcher In The Rye proves more than you don’t need a solid beginning to write a successful “classic” novel; you don’t need an ending, either. For all of his habitual line-stepping and social brinksmanship, you expect – if not a comeuppance – a kind of apotheosis, a moment of zen truth that sometimes happens with this author. Instead, after fainting from hunger and exhaustion, he visits a museum and a merry-go-round with Phoebe, then breaks off to explain he found his way home eventually and now thinks he is getting better in some general way.

How Holden found his way off his self-destructive path, if indeed he ever did, is left unanswered. The intimation is strong he hasn’t learned a thing.

I know I didn’t.

Of course, great fiction isn’t about answers. But there is a shape to how questions can be asked which is missing here, a sense of some thesis being explored, a conflict developed, a conclusion offered. Here, you get a dead end, like some très chic French existentialist novel, only instead of philosophy you ponder body odor and fingernail cuttings.

That

grottiness in Catcher In The Rye is part of its appeal; it broke some

boundaries. But two hundred pages of gross-out jokes and philosophical

shrugging wear out their welcome, or at least did for me. It was a surprise to

come back to a long-cherished book and find myself so disappointed by it, but that was the way this left me. It still amuses, but it frustrates me more.

No comments:

Post a Comment