A life in the New York Police Department is a kaleidoscope of the crazy, the deadly, and the profound. That’s even more true when you take on a generational view of the experience. Edward Conlon details his own time as well as those he has known among New York’s Finest.

Conlon came to police work seeing it as a unique type of employment, a vocation more than a job. People he grew up knowing, on both sides of his large Irish family, inspired him to think big:

I didn’t want to hear the story as much as I wanted to tell it, and I didn’t want to tell the story as much as I wanted to live it.

Conlon joined the police (technically its Housing Bureau, where he was initially assigned to the vast Claremont Village complex in the Bronx) with a background that included graduating from Harvard University and a non-profit stint rehabilitating criminals. He even wrote columns for New Yorker magazine. This background had me expecting a sensitive Serpico type. I was wrong.

While he admits to being a bit of a misfit, he’s foursquare behind the law. On the streets, engaging with suspects, informants, or witnesses, his agenda is about getting respect, both for himself and the badge he wears:

You have to be ready to shout, or at least show your teeth… I never made an empty threat and I never let anyone make one to me: if someone said they were going to hurt me, no matter how unimpressive the speaker or the speech, they would wind up in handcuffs or I’d wind up with a profound apology.

Had this book been written today, or even ten years later, I doubt Conlon would have been this frank. Writing right after the era of Mayor Rudy Giuliani, when proactive policing was still the thing and “no-broken-windows” a law enforcement mantra, Conlon extols a clear respect for law over touchy-feely concerns around civil rights.

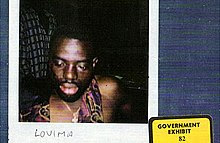

Not that race is never an issue; black and brown people can be suspicious and occasionally hostile with law enforcement officers, and Conlon’s book often deals with the uncomfortable fact they had good reasons. Long before George Floyd happened, cop violence was an issue. In 1999, undercover police shot innocent bystander Amadou Diallo 41 times in a stake-out before realizing they had made a mistake.

Conlon presents the Diallo killing as regrettable but not endemic. Blue Blood is full of examples of police doing right by citizens, and while Conlon doesn’t call out the races of everyone he saw being helped, his depictions are invariably that of good men and women doing a tough job under difficult conditions.

For him, race is more of a challenge of perception than anything else:

If you lock up someone who looks like you, you’re a race-traitor; if you lock up someone who doesn’t, you’re racist. In the end, the color of your skin doesn’t matter but the thickness of it does.

In the end, I was less affected by Conlon’s philosophy than his depth of experience, and his willingness to share everything he saw up close. Much of it was horrible. In the initial chapters, we look on at the misery of those on the margins, bookended by the lonely deaths of a cat and a dog. Addicts panhandle for money to commit slow suicide. Somehow Conlon finds himself unable to let go of the job, or as he calls it, the Job.

Blue Blood takes a while to get going; Conlon’s anecdotes about training and his early days learning the ropes stretch on and on. His family history is, at least at the outset, less fascinating than he seems to think. But about a third of the way through, this became tough to put down.

Conlon is a natural storyteller; it seems he’s got a new one on every other page. The book has a scattershot, episodic structure to it, aptly likened on a dust-jacket blurb to Michael Herr’s Dispatches. Like that book it starts out jagged, then begins to gather rhythm:

The Hole was run by a crew from down the block, and the junkies bought from them and sold for them, and the healthy, happy fatness of the dealers stood out as they hovered on the corner to supervise or to bring in new supplies to their cadaverous charges…

When you sign up an informant, you offer a new leaf, a new life, an appeal to the better angels in their nature. When an informant signs, however, he sees it as a deal with the devil, and though he’ll take his case or freedom for now, he knows that one day he’ll have to pack for the warm weather…

Not all of us find religion over the wandering years, but sooner or later, everybody gets to meet God.

Conlon’s father was an FBI agent; many others in his extended clan were New York City cops. Some were good cops, some weren’t. One great-grandfather, Sgt. Patrick Brown, “used to carry the bag on Atlantic Avenue,” meaning he lived well by taking bribes. Conlon spends ample time on what became of Brown, using his example to call out the temptations every cop faces.

Most set a higher standard. “Beneath the surface of the uniform, I saw a uniform substance, strong and caring and fair, if not always welcome when you were out with your friends,” he writes.

When he was young, Conlon clashed with his Fed father and his law-and-order mindset. He found himself running afoul of the law a few times, but eventually came to mend his ways. A product of a Catholic education, he recalls the example of St. Augustine, who found his way to righteousness while leading a life of sin. Damnation and salvation are never far away from each other in Conlon’s line of work.

“New York has always been full of heroes who are hard to like and villains who are hard to hate,” is how he sums it up, a sentiment which like many others here comes up again and again.

Conlon provides a penetrating look at how city police work evolved over the years, how it has been portrayed in the popular media, and alternately praised and damned by politicians. The Knapp Commission investigated corruption in the 1970s, affecting some change at the expense of sowing lasting distrust. Conlon examines the legacy of whistleblower cop Frank Serpico and how it came to define New York City policing in ways that cost the department more than good will.

He even references Robert Daley’s 1973 book Target Blue, and its depiction of a real-life police commissioner so adverse to bad press that he squashed efforts to stop a gang of cop killers because the perpetrators were black. “At one point, there was a single cop officially assigned to the investigation,” Conlon writes.

In the late 1980s, crack drove violent crime to epidemic levels (murders would rise to over 2,000 a year by 1990). That number had dropped dramatically by the time Conlon was on the beat, seeming to validate his law-and-order mindset, but drugs were still ravaging housing projects like Claremont Village. He writes about the addicts he worked to help after using them as informants. He also writes about the residents of these communities who took stands to clean up their neighborhoods.

By the end of the book, Conlon is working in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, sifting for human remains from the World Trade Center debris. His perspective is both gruesome and compelling:

We had white plastic five-gallon drums, and we filled them with bones. You got a feel for them, and after a while you could tell them from plastic molding or wooden sticks, but to be certain, you would break them. They had a certain give, unlike cable or a dowel. It felt sacrilegious at first, but it saved time.

There are many downer moments in Blue Blood, but some humor, too. One woman tries to have her husband arrested for adultery; told this isn’t against the law, she comes back with some New Yawk attitude. “No? Of course not – adultery is not a crime, ‘cause the men write the laws. I want female cops the next time!”

Cop life seems to require a lot of attitude, much dished out at one another. After a beloved squad commander is reassigned, Conlon clashes with his new bosses at the Street Narcotics Enforcement Unit (SNEU), who didn’t like his work methods and refused to issue his arrest warrants. While we only get his side of the story, it is a riveting sidebar that will remind many readers of their own working lives.

Finally Conlon got fed up and moved on: I remembered the line that went, “Hollywood is high school with money,” and wondered, “Is the Police Department high school with guns?”

In most cases, Conlon got along with people in his department, both those he worked with and those he served under. For a time, he found himself selected to be a speechwriter for the police commissioner, apparently related to his pedigree writing for The New Yorker. But the appointment never happened, and Conlon makes clear he never wanted it anyway. His heart was in the streets.

Blue Blood is a long read, and I did wonder where the editor was at points. He spends pages developing storylines that don’t resolve and tangents that slip into the ether. But as Conlon makes clear, resolutions are often lacking in real police work, and there are moments of epiphany amid the drudgery that he shares with the reader, letting us feel some of the same pulse beat of satisfactions and relief Conlon must have known in order to stay at his post each day.

No comments:

Post a Comment