Love isn’t horseshoes; there’s no scoring for landing near the mark. No one knew this better or communicated it more incessantly than Tennessee Williams, whose plays were epics of romantic frustration. One of his accessible and endearing, and at the same time perhaps the most depressing, is this.

Set deep in his classic time and place, the American South in “the first few years” of the 20th century, Summer And Smoke spotlights a pair of star-crossed next-door neighbors, she a uptight minister’s daughter, he a hedonistic heir to his father’s medical practice. She believes in God, he believes in medicine, but somehow these opposites not only attract but are impelled toward each other.

As Williams takes us from him teasing her in childhood to their adult selves having deep conversations about choosing between self-gratification and social obligation, you begin to wonder: should I root for them to be a couple, or to break free of each other’s spell?

Williams suggests proximity helps neither Alma nor John.

ALMA: I do declare, you haven’t changed in the slightest. It used to delight you to embarrass me and it still does!

JOHN: I guess I shouldn’t tell you this, but I heard an imitation of you at a party. [Scene One]

As the play makes clear from the beginning, Alma is stuck on John. Her feelings are not so much reciprocated but echoed; John seems more challenged by Alma, at first by her pity for his not having a mother, then by her determination to get him to improve himself. He keeps wanting to shake her up with his fiery independence; the more he tries, the more she proves her tenacity, miserable as it makes her.

The play has an energy and space to it that makes it stand out from other Williams plays I have read. A larger-than-usual cast fills out the world that Alma and John share with a number of townspeople. What they lack in dimension, they make up for in distinction.

Alma’s father is a rigid minister married to an infantilized bully who extorts the family’s embarrassment over her reduced mental condition to cadge ice cream and shoplift expensive hats. Alma belongs to a reading club where one shrill harpy rides herd on the tenderer sensibilities of her clubmates. John pals around with the town’s riff-raff, including a Mexican hottie whose crooked father brags about the jewelry he got for her at the point of a gun.

Not a subtle cast. But they are effective at creating a scrum of humanity against which Alma and John find themselves.

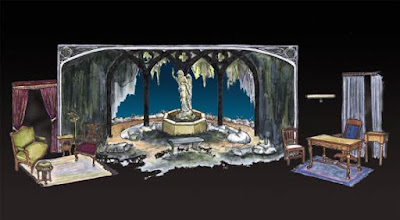

With twelve compact scenes, the play seems designed more for a movie than a stage production. It was made into a successful if largely forgotten movie in 1961, but also has a novelistic quality. Other Williams plays evoke a more claustrophobic feeling, like Suddenly Last Summer, set in an indoor garden, or Orpheus Descending, set in a shop. This play alternates between different rooms of two separate houses as well as an outdoor space nearby.

Williams had very clear designs regarding the play’s setting, which he lays out at the start:

There are no actual doors or windows or walls. Doors and windows are represented by delicate frameworks of Gothic design. These frames have strings of ivy clinging to them, the leaves of emerald and amber. Sections of wall are used only where they are functionally required.

He also is very specific regarding the female protagonist, Alma Winemiller:

Alma had an adult quality as a child and now, in her middle twenties, there is something prematurely spinsterish about her. An excessive propriety and self-consciousness are apparent in her nervous laughter; her voice and gestures belong to years of church entertainments, to the position of hostess in a rectory. People her own age regard her as rather quaintly and humorously affected.

Hence John’s comment in Scene One about hearing someone impersonate Alma at a party. She is as much of a social outcast as John. Deep down, she knows it.

Alma is the play’s centerpiece and clear hero, stubbornly defiant and yet very sensitive to how others view her. John’s digs at her piety are on target, given her fears of life and love and the frail shelter she finds from both in her dogma. Yet he’s no shining example of Nietzschean will to power; more a sail blowing in whatever direction there is a crapgame or a loose woman to be had.

So as they pick at each other’s lifestyle, both have a point:

JOHN: You think my character’s weak?

ALMA: I think you’re confused, just awfully, awfully confused, as confused as I am – but in a different way… [Scene Six]

John may be the reasonable one; his rebellion comes from a more intellectual place. He sees life as a cruel game as witnessed in the hospital wards where he helps his father fight infectious disease. He does get in his digs, pointing at an anatomy chart and asking Alma where the soul can be in such a place.

John threatens Alma’s beliefs, and there can be a powerful attraction in such a threat, especially when she looks back at her lost youth. But what draws John to Alma is harder to explain, and at the center of the mystery. “Many’s the time I’ve looked across at the Rectory and wondered if it would be worth trying, you and me…” he tells her.

That wistful sense of lost connection permeates every fiber of Summer And Smoke, giving it a haunting undertow. It’s not a subtle play, but Williams’s focus on the shifting tides of human feeling over a brief period of time packs a wallop. Whenever Alma and John are confronting each other, there is an elemental power about them, whether they are glimpsed briefly in childhood:

JOHN: Eternity. What is eternity?

ALMA: It’s something that goes on and on when life and death and time and everything else is all through with.

JOHN: There’s no such thing. [Prologue]

Or when they are confronting each other late in the play, having come around to each other’s points of view but no closer to one another:

JOHN: It’s best not to ask for too much.

ALMA: I disagree with you. I say, ask for all, but be prepared to get nothing! [Scene Eleven]

While

the characters’s philosophical dichotomy no doubt will strike some drama

lovers, and particularly fans of Williams’s succulent Southern Gothic gumbo of rawer

emotion, as lukewarm material for a play, the end result is satisfying on its

own terms. Summer And Smoke touches on major Tennessee Williams themes,

like sex, God, and loneliness, but its more grounded in its presentation of

life.

The ending offers the play’s strongest takeaway, hopefully ambiguous in one sense, sharply final in another. Love is the answer seems its message, even when its answer is no.

No comments:

Post a Comment