Ruling Britannia

Long before Great Britain became the world’s greatest empire, it was for 400 years a colony of another empire called Rome. What did Rome ever do for the British? Plenty, according to H. H. Scullard, including introducing moldboards to plows, paving to roads, and cats to homes.

There was also the creation of cities, specifically one at the mouth of the Thames River known today as London. If it wasn’t for war, famine, and slavery, all of which all had existed before the Romans came, one can see why the British regarded their colonization to be a blessing.

Especially when it was all over in a relative blink of an eye.

Early on, Scullard quotes the famous Roman historian Tacitus on how colonization went down: “And so, little by little, the Britons were seduced into alluring vices: arcades, baths, and sumptuous banquets. In their simplicity they called such novelties ‘civilization,’ when in reality they were part of their enslavement.”

It’s hard to see how the British got burned. Scullard makes a case for the positive, pointing out how the little that remains in evidence of Roman Britain speaks to improved farming, widespread wealth, and the growth of a comfortable middle class. The Roman villa revolutionized British agriculture the same way the cities brought order to society.

Scullard writes: The most striking change, which was to transfigure the face of Britain, was urbanization. Large or small, towns were an essential element in Roman Britain, and to a very considerable extent the deliberate gift of the Romans.

Around the third century, it was safer to be a Roman citizen in Britain than in Rome, with economic prosperity coupled with ample defenses both natural and artificial to prevent outside invasions. Yet when the end came, it did with sudden finality. Unlike other Roman possessions like Spain and France, Great Britain wouldn’t even get a language from their Roman overseers. Saxon invaders overrode all.

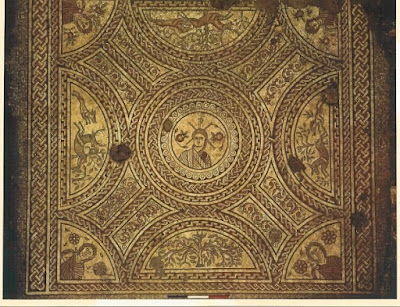

Scullard’s book is quite dry but splendidly organized. Each chapter takes on a single element of the larger story, such as the pre-conquest period or the economic underpinnings of the colony. A generous helping of maps, illustrations, and photographs are incorporated to highlight and augment relevant sections of the text.

Published in 1979, the book misses out on later archaeological finds like the discovery of a possible Roman fort at Cawdor, in the Scottish Highlands. Scullard does note signs of encampment in the Lowlands from an 81-84 A. D. invasion by Governor Gnaeus Agricola but nothing permanent. The failure to take Scotland, Scullard concludes, was “apparently inevitable unless further troops (legionnaires and still more auxiliaries) could be spared for this distant province at a time when the manpower of the empire was fully stretched.”

Scullard’s reports on then-recent findings are fascinating to read, including remains of temples, baths, gravestones, roof tiles, and other oddities, like curses preserved on wood tablets:

More detail and venom are contained in a second example set out in crude cursive writing and pierced by seven nails: “I fixed Tertia Maria and her life and mind and memory and liver and lungs mixed, fate, thoughts, memory; so may she not be able to speak secrets nor…” Time, if not this curse, has in fact preserved her secrets inviolate.

Rome’s conquest of Britain was initiated by Julius Caesar in part, Scullard claims, to squash the Druidic priests based there from sowing unrest in Gaul. But he settled for just the southeastern portion of the island. It would be nearly a century before Emperor Claudius, seeking both glory and mineral resources, made conquering Britain a priority.

This was easier done than maintained. The many Celtic tribes that occupied England and Wales soon rebelled against their new rulers. The most famous instance of this was the 60-61 revolt of the Icenis, led by the legendary Boudica. Scullard blames the “rapacity” of procurator Catus Decianus for triggering this unrest, and describes the extent of what followed from archeological discoveries:

Seventy thousand people were said to have perished in the sack of the three towns, and burnt debris and skeletons found at Spitalfields bear witness to the onslaught.

The Roman governor Suetonius would recover the initiative and crush the rebellion. Scullard notes the appointment of a new procurator, Julius Classicianus, would soften the effects of Roman rule on the population and usher in a more peaceful era of colonization.

After that, the Romans focused on holding what they had, surrounding their British possession with walls, most famously Hadrian’s Wall of the 120s, named after the emperor who commanded its construction. Eighty miles long, it is described by Scullard as a kind of city of watchtowers and forts supported by extensive roads:

A large ditch, 27 feet wide and 10 feet deep, was dug in front (i. e. to the north) of the wall, which was built by the legionnaires themselves, with inscriptions recording the lengths put up by individual working parties. The whole length was a continuous stone structure, though at the beginning (perhaps until 158) the western part was constructed out of turf. It was never less than 8 feet thick and 15 feet high, and at every mile there was a fortlet with gates to the front and rear providing ways through.

Later the Romans extended their northern boundary by building the Antonine Wall around the Firth of Forth, though this was abandoned after what Scullard claims were many Scottish attacks. After that, the Romans held on to England and Wales for three more centuries.

Scullard’s descriptions of Hadrian’s Wall is a highpoint of this book, with many engaging diagrams. He even puts the reader in the boots of the occupying army:

Officers could indulge in the comfort of a hot bath in almost “Mediterranean” housing conditions, but a Syrian auxiliary, far from his Oriental homeland, must have regarded service in Britain in a somewhat different light, especially when, after a night’s sentry duty, he gazed out from the Wall at dawn over the wild windswept desolation stretching away ever northwards into hostile territory.

Scullard even offers some analysis as to the fate of a fabled Roman legion, the Legio IX Hispana, once thought to have been wiped out defending Hadrian’s Wall and a subject of many works of fiction. By the time of Roman Britain’s publication, this had been refuted. Scullard spends some time laying out the historic record of this and other legions.

Even with its many illustrations, Roman Britain is not a colorful book. It is more of a set of lectures on different aspects of Roman colonization, expanding upon themes of religion, of diet, even the ruins of a lighthouse and adjacent naval fort found in Dover:

In

the second century, as recent excavations in the 1970s have shown, the

headquarters of the fleet was probably at Dover where its fort has been found,

together with some 800 tiles stamped CL(ASSIS) BR(ITANNICA). The fort was over

two acres in area and enclosed barracks and granaries; some of its walls

survive to the height of three meters.

Am I holding Scullard at fault for interesting but not satisfying me? That’s hardly the worst thing a historian can do. The prose is not engaging enough for a layman, and the text maybe not deep enough for the serious student. But anyone with a casual interest in the story of Roman Britain may enjoy this book enough as I did to want to probe further and learn more of this short if fruitful era.

No comments:

Post a Comment