Presidents are not well-balanced people. They go out of their way risking derision, abuse, even murder to affect miniscule changes in how things are; at best making compromises, at worst committing crimes. Such an impulse must be questioned; either they are corrupt or insane.

Few presidents wore that derangement so openly as Richard Nixon, a childhood misfit who ran for national office five times and looked more miserable and awkward each time at it. In a business that demands compulsive socializing, he was a proud loner who cultivated many strategic allies but very few friends.

Yet he made himself the most consequential president of the second half of the 20th century, an era which gave us several.

Tom Wicker, one of Nixon’s fiercer critics when he was in office, takes stock in this look back which is half-biography, half-memoir of “one of the two most interesting public men I have known. The other was Lyndon Johnson, who was not particularly likable either.”

The book’s title is a reference to Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim, when the narrator Marlowe looks at the disgraced Jim, and sees in him “not the product of oddly perverted thinking” but a man who belonged. Nixon was a perpetual outsider, shunned by richer kids at school and later by the liberal elites of postwar America. But his penchant for hard work and an understanding for how to get things done made him vitally effective.

In time, as president, he would implement policies that would have impressed many critics if only they had been accomplished by someone else. Liberals may have hated him, they just weren’t as different from him as they liked to think. Or so the liberal Wicker would have it.

One Of Us engages more as a treatise than a bio, an examination of realpolitik through the career of one of its most accomplished practitioners. The book is often tedious, especially when Wicker spends long chapters recounting battles he covered which Nixon wasn’t even in. But the core thesis is compelling and laid out with cool insistence.

Wicker examines his subject with a mixture of respect and pity:

Nixon’s political success appears to have been built on the calculated (however necessary) presentation of a public persona that brutally distorted the essential Nixon within – an introverted intellectual – though at what price to his self-esteem can only be imagined.

One Of Us is strangely laid out. The eight years he served as Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president gets vigorous attention. But Nixon’s most famous episode, the Watergate scandal that made him America’s first president to resign in disgrace, is barely skimmed. One episode Nixon haters loved to carp on, his crushing defeat in the 1962 California gubernatorial race, is almost completely ignored.

Wicker may never have liked Nixon, but he’s not out to bury him.

At the root of Nixon, according to Wicker, is a sullen failure to belong. Unable because of his poor roots to join the cool-kids club at Whittier College, the Franklins, he formed his own club, the Orthogonian Society, a name which roughly translates as “square shooters.”

A similar distrust of elites made him suspicious of New Deal politicians, particularly those he saw as ready to sell out freedom the way they had at the Yalta conference near the end of World War II. Anticommunism became young Nixon’s hobby horse, and he rode it all the way to Washington, elected first as a House member from California, then a senator, and finally vice president all before he was 40.

Nixon haters blame his willingness to play dirty politics against saintly liberal opponents, such as incumbent House member Jerry Voorhis in Nixon’s first race. Voorhis was “a good congressman,” Wicker writes, but a terrible candidate who found himself well to the left of his district:

In a game the ethic of which is to win, it should not be surprising that players will go to great lengths to win. Jerry Voorhis appears to have been a rare exception; Nixon certainly was not.

Nixon’s red-baiting was not as extreme or false as Joseph McCarthy’s; while distasteful to Wicker, he presents it as a product of the time.

Another example of supposed Nixon perfidy, the 1952 handling of an alleged slush fund, is firmly dismissed by Wicker. That year, he writes, Nixon was the only national candidate on either party’s ticket not making money off his public service. Dwight Eisenhower got a sweetheart tax deal on proceeds for a book. Democratic vice-presidential candidate John Sparkman carried his wife on his Senate payroll.

It was only by going on television and laying out just what items he did accept legally – including a dog named Checkers who he said, he was going to keep because his daughters loved him – that Nixon avoided a major effort by Eisenhower’s supporters to dump him from the ticket. It was a remarkable speech that saved his career, and yet it also made many people hate Nixon more. Wicker explains:

Instead, the speech has become legendary as a sort of comic and demeaning public striptease that cast Nixon forever as a vulgar political trickster who would disclose the most intimate private details and stoop even to exploiting his wife and his children’s dog to grub votes.

In the “Checkers” speech, Nixon made clear he wouldn’t go quietly, saying anyone running for national office should be as open as he was to disclosure. Wicker sees that as a none-too-subtle dig at Ike. The two winners never trusted each other in their eight years together. Wicker makes clear Nixon was not to blame for that and deserved better.

The core point of One Of Us, what will make it uncomfortable reading to some, is the way Wicker pushes back against the idea of Nixon as an ideological outlier, either within his own party or among all national leaders during his time in the public spotlight. Interventions in other nations were common in the 1950s and 1960s, whichever party controlled the White House. Nixon as president only continued that.

Wicker writes: Nixon’s was “situational morality,” not a fixed and accepted code of conduct; and the same might have been said, in much of the postwar era, of American foreign policy.

Today, Nixon is often called the architect of the “Southern strategy,” a clandestine, successful effort to make the South a Republican bastion by catering to racist sentiment. It is emerging today as his unchallenged legacy in American academia. Wicker pushed back on this decades ago, by calling out his record as President:

Richard Nixon received little credit then, and probably gets less today, for having overseen – indeed, planned and carried out – more school desegregation than any other president, and for putting an end, at last, to dual school systems in the South.

Nixon’s call for “law and order” and against forced busing in the 1968 election was seen as racist dog-whistling, but the substance of his presidency was ending legal segregation in line with the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education ruling, which Nixon had always supported.

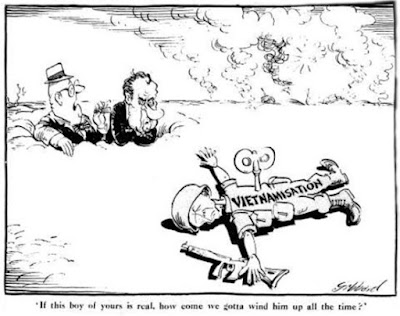

In other areas of Nixon’s presidency, Wicker is more critical, even withering. He can’t blame the guy for Vietnam (Nixon was indeed “one of us” that way, carrying on a war inherited from Lyndon Johnson which had American involvement since Harry Truman’s time), but he makes clear Nixon and his chief diplomat, Henry Kissinger, did some nasty things in the name of peace, like killing Asian civilians in 1972:

Nixon was bombing Hanoi to persuade Saigon to accept the October agreement. The North Vietnamese were taking a terrible pounding and high casualties to impress [South Vietnam President] Nguyen Van Thieu with Richard Nixon’s sincerity.

Wicker is similarly scornful of how Nixon and Kissinger went about their other major diplomacies, the signing of a nuclear arms treaty with the Soviet Union and the opening of Red China. Still, he has to admit the results of those were beneficial, if superficial to his gimlet eyes.

Wicker is no fan, but his willingness to give Nixon props in some places and push back on his harshest critics commands respect. This is a book he readily admits would have displeased many fellow journalists.

Wicker is certainly not with the conservatives, many of whom did have their own bones to pick with Tricky Dick. Nixon sold out South Vietnam and Taiwan, not to mention the gold standard, all things he could do because his anticommunist credentials needed no burnishing.

For that, Wicker admires Nixon’s ideological flexibility. He recognizes, like William Safire in his more admiring but still critical Nixon tome Before The Fall, a moderation at the heart of Nixon’s policies: He had been elected as a centrist…A centrist, I believe, he was to remain.

Wicker’s book is not a reference source for Nixon the man or his time on the national stage. He assumes the reader knows much of the story going in. In many ways, it is more of an extended column written by a longtime pundit who often uses Nixon’s story as an excuse to recall his own time in the trenches.

Our

37th President may have been thought of as the ultimate outsider,

both by others and himself. Wicker’s conclusion is that in his self-made outsider role, he served his country

better than many realized: “the American people may want more from the White

House than Nixon the man ever promised, but they usually get considerably less

than Nixon the president delivered.”

No comments:

Post a Comment