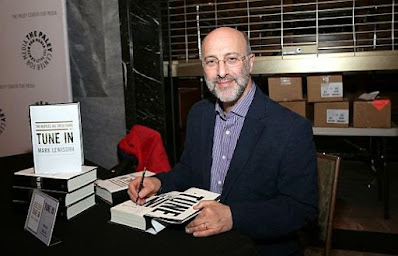

The truly fab thing about this book is how close Mark Lewisohn makes you feel to the Beatles, not as a musical legacy or cultural institution, but human beings you get to know better than just about anyone you will ever meet.

Yet it keeps reminding me of that old maxim: never meet your heroes.

To put it plainly, these guys played rough pushing their way to “the toppermost of the poppermost.” Most people picking this book up will know the sad tale of Pete Best, but many others were used and discarded for much less cause. “The Beatles weren’t sentimental types,” Lewisohn writes, in his typically understated way.

Subtitled “Vol. 1” as Lewisohn plans to carry forward the Beatles story in two more volumes at least as far as their 1969 break-up, Tune In begins by introducing us to the maternal and paternal ancestors of John, Paul, George, and Ringo, who were of English and Irish descent. Then we get to know the four growing up, not knowing each other for some time.

They grew up tough and hard, their cherubic faces hiding mischief and occasional cruelty. The streets of Liverpool bred much of their rough manner, but also a humor and a clear sense of purpose that would serve them well in time, individually and collectively.

Liverpool, writes Lewisohn in a preface, was “a scene in which the Beatles were sharper-smarter-faster-funnier than their many rivals – and where they also polished, well before they had hits, that tightly engaged relationship with their public. In other words, those later world-changing Beatles are these Beatles, just lesser-known, local not global.”

John Lennon would be their leader and motive force, though the first connection was made by Paul McCartney and George Harrison back in grade school. Music eventually put them into contact with John, a shared love of American rock ‘n’ roll in its more R&B-influenced form, though they started out as a skiffle band, playing washboards and tea chests and not too very well at that. John couldn’t even tune his guitar.

But something was happening, something Paul picked up at once the first time he saw John and his band, the Quarry Men, performing “Come Go With Me” at a church fair in Liverpool’s Woolton parish.

Lewisohn heard it, too, on a surviving recording made that day:

Singers always start off as impersonators, mimicking whoever made the record they’re performing, some perhaps going on to develop their own voice. That John Lennon already had it at Woolton, that he was so audibly himself, is the mark of a true original.

Lewisohn often steps back in his narrative to comment on surviving audio the same way he did in his great book The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions. His music perspective is not only engaging and warm, but a welcome break from the dreariness of the story itself.

The book stops at the end of 1962, between the recording and release of the song that kicked off their wider fame, “Please Please Me.” Until the Beatles get to Hamburg, West Germany in 1961, their first big outing as a professional outfit, Tune In suffers from a case of the slows. Not a major one; Lewisohn is charged with deeper purpose and always engaging in the margins. He untangles such things as the history of the Quarry Men, John’s strange parentless childhood, and how Paul and George found each other despite their different grade levels to become friends.

But the narrative often gets bogged down in the same sense of purposeless that seemed to affect John, Paul, and George as the Quarry Men faded with the demise of skiffle. The only future Beatle moving forward musically for most of this book is Ringo, a bit older than the others and much more musically advanced. He got professional gigs as a top drummer for Liverpool club bands while the Beatles busked around.

Ringo is the one apart from the others, not only from not being in the band until 1962 but for the way he grew up, much poorer than the others and kept from regular schooling because of chronic illness. He discovered drumming in a hospital after making one of many miraculous recoveries; as Lewisohn notes, “it was love at first strike.”

Ringo gives these 800 pages something it desperately needs, a rooting interest. None of the other three Beatles come off as well as people.

What made the Beatles great? For Lewisohn, the more challenging question through much of the book is what made them listenable.

Lewisohn draws on many sources, including a bass player they tried to recruit from another band: “They weren’t very good. In fact, they were really bad. John knew I played bass and asked if I fancied playing with them but I said, ‘Sorry, I’m in an established group, a good group.”

They would claim “the rhythm’s in the guitars,” because for much of this book the Beatles did without a drummer, too. Even when they got one they couldn’t hold onto him long. When Tommy Moore joined them for their first professional tour, in Scotland in 1961, Paul and George looked on with amusement as John picked on the quiet Moore for being slow.

Moore lost several teeth and had to be hospitalized when the Beatles’s van crashed. His bandmates pulled him out of his recovery bed to make the next show. Lewisohn relates:

He sat behind his kit that night battered and bruised, his face inflamed, his lip stitched, his mouth missing teeth – and, as he would relate, every few minutes John turned around and howled with glee at his misfortune.

What did make the Beatles good enough to be great in the end were twofold, as Lewisohn explains it. First, they could harmonize amazingly well for a club band, even when only George was trusted with a guitar solo. Second, they marinated themselves in the right kind of music.

Lewisohn excels in explicating this, spending time on the various musical crosscurrents wafting over the rooftops of Liverpool and in the aisles of the local Nems record store managed by Brian Epstein. Not only the usual suspects like Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Elvis and Carl Perkins, but others, too, like Arthur Alexander and the Shirelles’s “Will You Love Me Tomorrow.” Lewisohn elaborates on that last one:

This one record effectively launched the “girl-group sound” – R&B with beat, rhythm, melody and harmony – and no musical force beyond rock and roll was ever as crucial to the Beatles’ development.

Some Beatles myths are put to rest by Lewisohn, like John and Paul’s contention they wrote over a hundred songs before they found success. They wrote only a handful, and hardly any for a couple of years, preferring to cover the B-sides of American singles.

One song they did write, or rather Paul did, was called “Like Dreamers Do.” They never recorded it commercially, yet it might have been more responsible for their fame than any single they did put out in stores. That was because a man named Kim Bennett, who worked for song publishers Ardmore and Beechwood, took a fancy to it when he heard it on a failed audition acetate. He thought the Beatles had potential, not as performers, but writing songs for more commercial artists.

It is a fascinating tale, the bombshell among many firecracker revelations for those of us who thought we knew how Beatlemania started. It sure wasn’t because EMI producer George Martin took a shine to them; the Beatles were forced on Martin and he was initially unimpressed. Then when the Beatles did record a single, it was Bennett pushing it to the top, or to #17 on the charts, which was something.

“Kim Bennett had moved heaven and earth to help make ‘Love Me Do’ a hit,” Lewisohn writes. “No man could have done more, and George himself did a lot less.”

Martin did come around and became an early champion of the band, enough to ditch plans to have an outsider write songs for them. He also gave the final push to the most important piece of the Beatles’s puzzle when he urged they find a new drummer. Pete Best was great in Hamburg, but his four-in-the-bar style wouldn’t get them on the radio. Fortunately George Harrison knew just the guy, and the rest was history.

The back cover of my paperback edition states: “If you’ve never read a book about them, start here.” That is bad advice. Tune In is a super-fun book, but nearly any other Beatles book is a better place to begin reading about them. If you haven’t read dozens of other Beatles books or memorized your old videotape of The Compleat Beatles, you could well be put off by Lewisohn’s knowing allusions or resonances of coming glories.

Lewisohn buries you in day-by-day detail and endless interview excerpts from those who knew them. As George once sang, it’s all too much.

Lewisohn writes about the amazing serendipity of the Beatles’s journey, its teasing tendency of suggesting a friendly cosmos playing a hand. But they don’t come across here as particularly deserving recipients of such karmic largess. John is recalled offering brotherly sympathy to one of his young female fans, but he’s also given to moments of terrible cruelty as Paul and George giggle by his side. “John hardly ever said sorry and the others hardly ever muttered it on his behalf: the victim would be left to laugh it off or lick his wounds,” Lewisohn writes.

In

Ringo they found a rare comrade who could hang with them, and give as good as

he took, while his drumming raised their game enough to eventually prick the

ears of the world. This book is about getting to that point, alternately

exciting and enervating. The best was yet to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment