Before the 1960s created a new reality, Great Britain was a bleak and unpleasant land of rigid social structures, obtuse attitudes about life, and narrow opportunity, where the only escape was via the imagination.

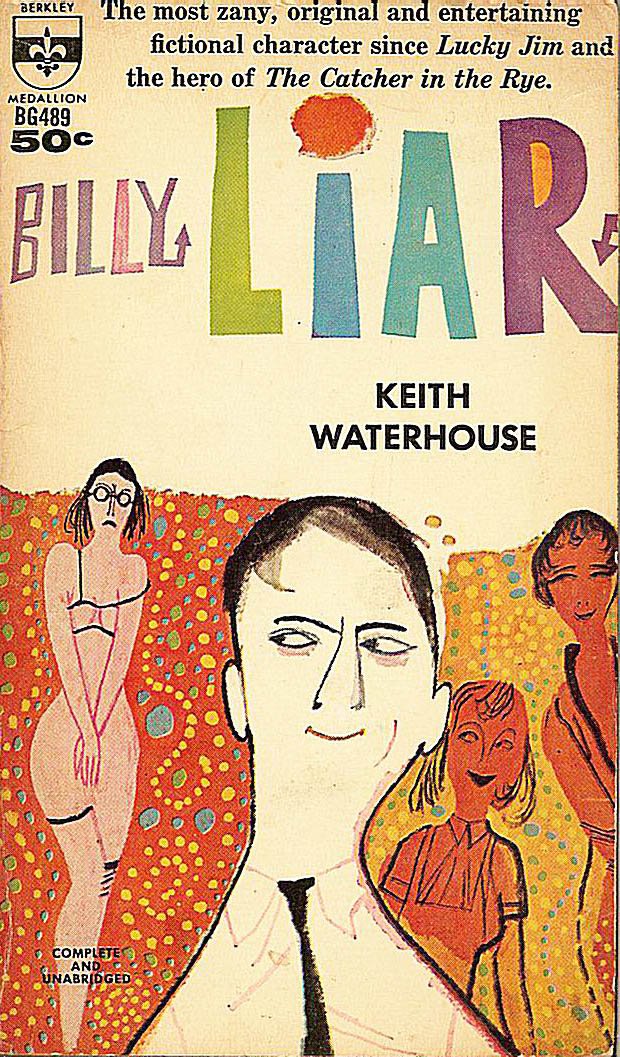

Before the 1960s created a new reality, Great Britain was a bleak and unpleasant land of rigid social structures, obtuse attitudes about life, and narrow opportunity, where the only escape was via the imagination.This is the Great Britain that is the subject of Keith Waterhouse's landmark 1959 novel, which became more influential as a play and even more influential as a movie.

Does it hold up today as something other than a period piece?

The novel is told in the first person by protagonist Billy Fisher, a young man from a Northern English town called Stradhoughton who is going nowhere in a hurry. He works as a clerk at a funeral parlor, and does a bit of stand-up at a local music hall, but saves most of his energy for exercising his imagination, both in a series of involved and elaborate daydreams as well as in a web of casual lies and deceits that net him three girlfriends and a whole lot of trouble.

Angry Young Man fiction was much the thing when Billy Liar was published, yet it should be said that Billy isn't particularly angry, only constrained, and that more by his own lethargy than the class system which still gripped English life. Billy has options, limited perhaps, but more than he cares to exercise.

"There were long periods of time when my only ambition was to suck a Polo mint right through without it breaking in my mouth; others when I would retreat into Ambrosia and sketch out the new artists' settlement on route eleven, and they would be doing profiles of me on television, 'Genius – or Madman?'"

Ambrosia is the land Billy has invented for himself, a kingdom of his mind where people love him for his battlefield heroics and brilliant leadership. Billy's retreat into these private fictions makes Billy Liar read at times more like James Thurber than John Osborne. He can't get past the first paragraph of an attempted novel, fret as he does about how his name should appear on the author's page. At times he imagines himself cutting a figure at a newspaperman's bar, amazing phantom colleagues with sparks of brilliance they ask to use in their columns.

The problem is that when the poor lad spins yarns, he often leaves a trail of angry victims behind. Imagination is a loaded gun in the hand of Billy Fisher. As the novel continues, a portrait of the subject as young sociopath begins to take shape, particularly when he comes into contact with one of the three women he is currently involved with, a "scruffy-looking" character named Liz who, alone among all the people in Billy's life, seems the captain of her own soul. Billy is attracted to Liz, but true commitment lies beyond his ken:

"I had no real feeling for her, but there was always some kind of pain when she went away, and when the pain yielded nothing, I converted it, like an alchemist busy with the seaweed, into something approaching love."

Liz, nicknamed "Woodbine Liz" by Billy's friends after a cheap but strong brand of cigarette popular in Great Britain at the time, is converted into a luminous sprite by Julie Christie in the 1963 movie adaptation; so powerful is Christie's presence that it kind of pulls the viewer from the story presented in the novel. In the novel, as much attention is drawn to the two other women Billy juggles, a waspish cafe waitress named Rita ("she had been voted The Girl We Would Most Like To Crash The Sound Barrier With by some American airmen") and an orange-eating prude named Barbara, whom Billy calls "the Witch" while plotting to steal her virginity. Already caricatures in the novel, they become more pronouncedly so in the movie.

I can't say I prefer the film to the novel, but it does seem a mite less cruel. In the novel, so many bad things happen to Billy in the course of this one day that it feels like author abuse after a while. The movie actually boils away some of the excess, like an embarrassing stand-up performance that exposes Billy's poor prospects as light entertainer. The hatred Billy seems to bring upon himself in the novel is somewhat muted in the movie. You also get director John Schlesinger working up the fantasy elements of Billy's life wherever he can to brilliant comic effect.

The novel isn't as bright and engaging as the movie; the fantasy sequences tend to reinforce our sense of Billy failing at life more than how much fun a place this Ambrosia of his might be. What the novel does have is a weightiness regarding Billy and his fading place in the world, a boy already falling behind in life who doesn't know how to deal with the race other than run backwards.

Waterhouse's novel develops this theme both for its humorous and tragic overtones. Billy is the sort of fellow who can't get out of bed without contemplating the length of his thumbnail or the "overpowering feeling that my fingers were webbed, like a duck's" and annoys his family to no end. Yet when he faces real tragedy, like a sudden death, his same inability to react with any recognizably human emotion makes him seem rather ruthless as well as clueless.

It is in this way, as well as in the affecting finale (the one element of the novel which actually is rendered bleaker in the movie) where Billy Liar scores over and above its reputation as being representative of a particular time and place. People fail to connect with one another all the time, and the more time passes, the more ways we discover to keep separate from those aspects of life we don't like. Today, Billy Fisher would be at his computer, no doubt blogging away. The symptoms change but the disease lives on.

The novel is told in the first person by protagonist Billy Fisher, a young man from a Northern English town called Stradhoughton who is going nowhere in a hurry. He works as a clerk at a funeral parlor, and does a bit of stand-up at a local music hall, but saves most of his energy for exercising his imagination, both in a series of involved and elaborate daydreams as well as in a web of casual lies and deceits that net him three girlfriends and a whole lot of trouble.

Angry Young Man fiction was much the thing when Billy Liar was published, yet it should be said that Billy isn't particularly angry, only constrained, and that more by his own lethargy than the class system which still gripped English life. Billy has options, limited perhaps, but more than he cares to exercise.

"There were long periods of time when my only ambition was to suck a Polo mint right through without it breaking in my mouth; others when I would retreat into Ambrosia and sketch out the new artists' settlement on route eleven, and they would be doing profiles of me on television, 'Genius – or Madman?'"

Ambrosia is the land Billy has invented for himself, a kingdom of his mind where people love him for his battlefield heroics and brilliant leadership. Billy's retreat into these private fictions makes Billy Liar read at times more like James Thurber than John Osborne. He can't get past the first paragraph of an attempted novel, fret as he does about how his name should appear on the author's page. At times he imagines himself cutting a figure at a newspaperman's bar, amazing phantom colleagues with sparks of brilliance they ask to use in their columns.

The problem is that when the poor lad spins yarns, he often leaves a trail of angry victims behind. Imagination is a loaded gun in the hand of Billy Fisher. As the novel continues, a portrait of the subject as young sociopath begins to take shape, particularly when he comes into contact with one of the three women he is currently involved with, a "scruffy-looking" character named Liz who, alone among all the people in Billy's life, seems the captain of her own soul. Billy is attracted to Liz, but true commitment lies beyond his ken:

"I had no real feeling for her, but there was always some kind of pain when she went away, and when the pain yielded nothing, I converted it, like an alchemist busy with the seaweed, into something approaching love."

Liz, nicknamed "Woodbine Liz" by Billy's friends after a cheap but strong brand of cigarette popular in Great Britain at the time, is converted into a luminous sprite by Julie Christie in the 1963 movie adaptation; so powerful is Christie's presence that it kind of pulls the viewer from the story presented in the novel. In the novel, as much attention is drawn to the two other women Billy juggles, a waspish cafe waitress named Rita ("she had been voted The Girl We Would Most Like To Crash The Sound Barrier With by some American airmen") and an orange-eating prude named Barbara, whom Billy calls "the Witch" while plotting to steal her virginity. Already caricatures in the novel, they become more pronouncedly so in the movie.

| Billy (Tom Courtenay) and Liz (Julie Christie) have a heart-to-heart talk in John Schlesinger's film adaptation of Billy Liar. As in the novel, Liz is the only person Billy can open up to, though she's not as much an avatar of hopefulness as she becomes when played by Christie, in her film debut. [Photo from www.theguardian.com] |

The novel isn't as bright and engaging as the movie; the fantasy sequences tend to reinforce our sense of Billy failing at life more than how much fun a place this Ambrosia of his might be. What the novel does have is a weightiness regarding Billy and his fading place in the world, a boy already falling behind in life who doesn't know how to deal with the race other than run backwards.

Waterhouse's novel develops this theme both for its humorous and tragic overtones. Billy is the sort of fellow who can't get out of bed without contemplating the length of his thumbnail or the "overpowering feeling that my fingers were webbed, like a duck's" and annoys his family to no end. Yet when he faces real tragedy, like a sudden death, his same inability to react with any recognizably human emotion makes him seem rather ruthless as well as clueless.

It is in this way, as well as in the affecting finale (the one element of the novel which actually is rendered bleaker in the movie) where Billy Liar scores over and above its reputation as being representative of a particular time and place. People fail to connect with one another all the time, and the more time passes, the more ways we discover to keep separate from those aspects of life we don't like. Today, Billy Fisher would be at his computer, no doubt blogging away. The symptoms change but the disease lives on.

No comments:

Post a Comment